It was President Ferdinand “Bongbong” R. Marcos Jr. himself who recently admitted that cracking down on corruption—particularly in flood-control projects—is no simple task. He likened it to a major cancer surgery: painful but necessary before any healing begins.

More than 138 years ago, our national hero, Dr. José P. Rizal, diagnosed the same disease. In his classic novel Noli Me Tángere, translated into English as The Social Cancer, he warned that the nation was infected with abuses, deceit, and oppressive “delicate things” that slowly consumed the country. Rizal compared corruption to a malignant cancer—silent, aggressive, and destructive from within. A century and a half later, the same illness still plagues our people, especially the poor.

President Marcos further emphasized: “But we are trying precisely to change the entire system. And when you have to excise a cancer out of such a complicated system, you need to do some very major surgery. And to do that, and when you do that, you will bleed. And that is what we had to go through.”

His metaphor suggests a painful transformation ahead. Does he refer to drastic measures—coup d’état, martial law, or insurrection? We cannot know. But one truth is clear: corruption will never be eradicated, nor even meaningfully reduced, by elections alone.

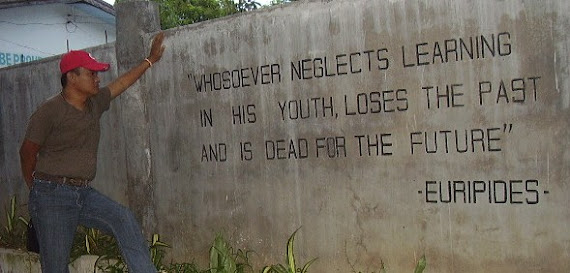

Rizal taught that the surest cure begins with a people who are educated, aware of their rights, and unwilling to be deceived. Leaders must live morally upright lives, for personal example is the most powerful teacher. Laws must be strong, institutions must be honest, and public service must be guided by justice rather than favoritism. A free press and the courage to speak truth keep abuses from festering in the dark. Above all, every Filipino must love the country more than personal gain and must reject even the smallest act of dishonesty. For Rizal, the deepest reform starts not in Malacañang, but in our own hearts.

Noli Me Tángere reminds us that corruption thrives where power is concentrated in the hands of a few who face no accountability. In the novel, corrupt friars and officials maintain control through fear, flattery, and manipulation of information. Yet Rizal also exposes another painful reality: corruption survives not only because of abusive leaders, but because of the silent acceptance of those who feel powerless or afraid. Silence is the life support system that keeps corruption alive.

Today, as in Rizal’s time, the cure requires courage from both government and citizenry. We must demand accountability, not just promises. We must cultivate integrity, not just outrage. Democracy is not a spectacle we watch every three years—it is a daily commitment to truth and responsibility.

And so the ultimate question confronts us: How do we finally cure the social cancer that has tormented our nation for generations?

The

answer begins with the same wisdom Rizal left us: education, vigilance, moral

leadership, and a people who refuse to surrender their dignity. Only then can

the Philippines rise—not merely from surgery—but into lasting health.

No comments:

Post a Comment